3 Teeny Tiny Case Studies of Marketing Turnarounds (Mmmm, Bud Light)

And a note about my old apartment

Hello Gobbledeers,

I hope you’re well. Today we’ll talk about:

Sometimes you’re a CMO at a company that needs a turnaround. Here are 3 ways you might have even a tiny chance of doing that successfully.

We lost one of the good ones this week.

Also, we just hit 2,500 subscribers. All organically. Thank you to everyone who told their friends about Gobbledy. It means a lot.

But first, my ad about me:

Here’s where I tell you that I work with companies on their messaging (2-day workshop to build out what you should say on your website, or I can look at what you’ve already got). I’m at jared@sagelett.com if you’d like to chat.

Maybe there is a way to save a struggling company

Chief Marketing Officers generally find themselves in one of these two situations:

Situation 1: You have a job. And that job is Chief Marketing Officer.

Situation 2: You do not have a job.

If you find yourself in Situation 2, don’t panic. You’ve been a CMO - that’s great! You have lots of options. I’m sure something will work out. You should be picky! Don’t just take the first job that comes along at a flailing company that fired its last 2 CMOs. That’s a sucker’s move! I mean, obviously you’ll END UP doing that. But don’t start there. Have hope!

If you find yourself in situation 1, there are actually 2 sub-situations you may find yourself in:

Situation 1a: You have a job. And that job is Chief Marketing Officer. And the company is not imploding. This is a plum job. Please don’t lose this job. It may seem like your job is terrible and making you wish you had listened to your father and become a lawyer, but I promise - those people are wishing they hadn’t listened to their father who, they now realize, drank every night because he hated his job.

Situation 1b: You have a job. And that job is Chief Marketing Officer. And the company is currently imploding. And now the company thinks that you are going to fix 14 years of bad decisions. In 18 months. Godspeed.

Today, I wanted to present 3 very mini case studies for Situation 1b:

Peloton

The current poster child for Situation 1b is Peloton, which, after creating a product that people absolutely loved - to the point where they created “Peloton rooms” in their homes - found themselves in a near-death spiral after COVID-era demand dried up. (Though I guess people had Zoom rooms too, and look how that turned out.)

They responded to this situation with a “shrink yourself into profitability” strategy (Simpsons fans know this as “smoke yourself thin.”) Amazingly, they were not able to shrink themselves into profitability.

So they blew through a few heads of marketing, but they now have a new head of marketing, and she recently shared her ideas for turning the company around with the Wall Street Journal. The strategy is two-fold:

Fold 1: “Convey that Peloton is a suite of services for a range of customers with varying fitness goals—not just a stationary bike seller. The target: particular groups of consumers that show sales potential, such as millennial men, some of which view the company as a women’s brand.”

Fold 2: "The company hopes that the marketing pivot, employed with less marketing spending than in the past, will generate more demand for its full range of products.”

So - the plan is to target an entirely new market, one that very specifically thinks the brand is not for them, and the company believes in this strategy so much that they will spend LESS on it than they have on past strategies and that specifically by spending less (that can’t be right?) it will generate more demand.

Key takeaway: If your company is imploding and cutting your marketing budget, but you have a core set of customers who love you to the point where they created rooms in your house for their product, please deploy your limited marketing dollars on getting more out of your current customers, because you will not be able to spend enough to find a new consumer.

Stitch Fix

Subscription box o’ clothes company Stitch Fix has also been in a spiral since COVID and they, too, have a plan. Their first plan - go two years without a head of marketing - worked splendidly. Then, they hired a new CEO from Macy’s, a company that is responsible for 2 of my favorite headlines/quotes about a retailer:

Except that everyone hates their products and their stores, Macy’s is in great shape!

I’ve also enjoyed the litany of excuses they’ve given over the years for why business has been bad. This one is my favorite:

In that case they missed their earnings because the weather was too cold and too warm.

Anyway, Stitch Fix brought on a new CEO from Macy’s who, to say the least, has his work cut out for him. And he actually has a plan and the plan actually makes sense. Which is amazing (and shocking, considering, y’know, Macy’s.) The plan is (in short): cut about $100 million in expenses (“smoke yourself thin”), then build, then grow. And the CEO isn’t promising any miracles, noting recently on an earnings call, “As I’ve stated before, and we’ll continue to share, transformations take time.” He added that the company plans to return to growth by 2026, something that will 1000% not happen by 2026.

Now, the company is actually doing real work here - $100 million in cost savings isn’t nothing. They’re building out their private label brands (ie, they’re trying to sell more of their higher margin products). They’re keeping the foundation of their business (subscription boxes of clothes), while removing some of the profit challenges of that model (you can now get more than 5 items of clothing in a box…and based on the number of items of clothing that show up at our apartment on a weekly basis, I’m guessing that is a change that will appeal to their customers).

But I do get nervous when I read stuff like this:

“Much of that work is already underway, including changes to the customer experience and an updated logo. Stitch Fix has begun to include stylist photos and personalized notes in new digital style cards in some boxes…”

Key takeaways:

A turnaround has a better chance of succeeding if its rooted in building upon the fundamentals of your business, rather than saying that you want a whole new type of customer. If Stitch Fix has any chance of success, it will be because they’re able to send people clothing they actually like (gasp!) at a profit margin that makes sense for the company (gasp 2!). This is roughly the model employed by possibly-the-greatest-apparel-turnaround-story-ever Abercrombie & Fitch, which was left for dead…until 10 years ago, when they began a 5+ year transformation not unlike what Stitch Fix is trying, where they focused on stripping out all of the garbage of their past (sexual harassment accusations against the CEO, first & foremost), and embracing their DNA (great preppy clothes that attractive 20somethings can wear every day). The turnaround is remarkable, but it takes 5-10 years.

If you are a CMO at a company where the CEO is coming in to rebuild the business, always pitch a new logo. You won’t get fired for a new logo.

Bud Light

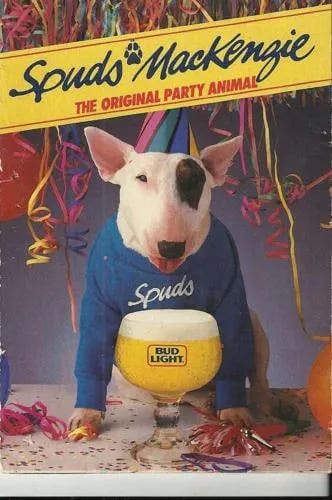

In case you’ve been under a rock - Bud Light did something remarkable last year: it destroyed its business with one, tiny marketing campaign. Bud Light had previously been known for marketing campaigns like this one:

Who can hate a dog that likes a party?

Anyway, fast forward, blah blah blah, transgender influencer, blah blah blah, Kid Rock, blah blah blah, $1.4 billion drop in revenue, blah blah blah, market share dropped by half.

OK, you’re caught up.

You may also remember that Target found itself in a similar (though not as dramatic) situation.

If you find yourself running marketing at a company where you are embroiled in a culture wars controversy, I believe you have 3 options.

Option 1: “We don’t care what you think, we believe strongly in this cause, and everyone who doesn’t can go F themselves.” Nobody chooses this.

Option 2: Slink quietly away and hope that everyone forgets about the #takepride displays you had in your stores, except that one of your key customer bases absolutely will not forget about it and they will be very pissed off that you abandoned them, even though you probably had to abandon them because your same store sales collapsed and you’re a public company.

Option 3: Take the George Costanza approach and do the opposite. As Jerry says to George in that Seinfeld episode: “If every instinct you have is wrong, then the opposite would have to be right.” Hard to argue with that! And so that’s what Bud Light has done:

What’s the opposite of having a transgender influencer hawk your product? Have Shane Gillis hawk your product and go on Joe Rogan to talk about it. Also there’s a commercial, but really, you don’t need to see it.

Key Takeaway: Target should’ve stocked more Make America Great Again hats.

And a final note…

We live in New York City, and one of the things I say about living here is that the things that are awful about living here are truly awful, and that the things that are amazing about living here are uniquely amazing.

My family and I lived in a uniquely amazing building for about 10 years on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. New Yorkers are often accused of being unfriendly types who keep to themselves and would never interact with another New Yorker, but the building is, truly, a community.

We had Halloween parties and gatherings on the roofdeck. When the storm Sandy shut down the city years ago, the kids in the building all hung out in the lobby and played games together for days. And each Christmas the building put on a little party in the lobby for the 80 or so people who lived there, and the children of the building would sit on the laps of the somewhat older children in the building and watch as building residents performed.

Musical theater performer (and Tony award winner) Gavin Creel lived in our building and would sing each year with children’s musician Laurie Berkner, who also lived there. My wife and I would sit and listen to them and talk about how amazing it is that we live in a building where it’s a real community, where we’ve all gotten to know each other. Where other buildings we’ve lived in have no personality, no community. Ours did. And the people who chose to live there embraced it.

If you hadn’t read about it, Gavin passed away this week after a short illness. He was the type of person who made you feel like he was one of your closest friends, even if you were not. And from the outpouring we’ve seen this week from the theater community, apparently everyone felt that way.

We knew him as someone who would always - always! - stop and chat. Who would invite us backstage when he performed. Who sang at the Christmas party. Who would hang out with the kids. Who let me play piano while he sang. Who would sit with us on the roof while we were having dinner. Who asked my in-laws to come backstage and chat after performing in Florida. Who told his friends that they, too, should buy an apartment in our building because the community was amazing (and they did).

And everyone there loved him back. I was just looking at a photo that we took the day after he won the Tony Award where the kids in the building drew pictures with crayons to congratulate him, and covered his door with the pictures so he’d be greeted with them when he came home.

Living in NYC is uniquely amazing because of the people who make up the community around you. Our old building had so many who added so much, and who I never could have met any other way (the NY Times reporter, the violinist in the philharmonic, the actor, the activist, the Holocaust survivor, the doorman who told me about getting to meet the Pope…) It was made up of people who chose to be in that community, and contribute to it, even though as New Yorkers they had every right not to.

Gavin chose to make the place we all lived a little better. What more could you want from a neighbor?

As always, thank you for reading to the end.

Happy Rosh Hashanah to those of you celebrating.

I’m always happy to chat.

And finally, congrats on the 2,500 subscribers and remaining a pure play.

https://youtu.be/BzAdXyPYKQo?si=W-TTcYncZ1W8QF9q

I think you meant to write Happy Rosh Hashana to my Jewish readers of the Hebrew faith.