There are actually effective ways to use death as a marketing strategy

And shhhh, please keep quiet while you're reserving chairs at the pool

Hello Gobbledeers,

How’s it going?

First, a friendly reminder:

I’m holding a session I’m calling “Everything You Need to Transform Your Homepage Messaging (in 45 minutes”.) It’s not a webinar - it’ll be interactive (ie, you can ask questions). I’ll walk through the structure of how you can hold your own messaging workshop at your company, including who needs to be there; each session of the workshop and who leads it; and how to turn the output into new messaging.

Basically, I’m sharing everything I’ve learned from doing these workshops with you, the Gobbledy readers.

Oh, you’re thinking, when is this happening? That’s a great question! It’s on Thursday, May 15th, at 2pm Eastern time. It’s free, and I promise it’ll be fun and useful. Hard to beat that combination. The response so far has been beyond my wildest expectations - I’m so excited for the session. Register here.

Next, if you missed last week’s Everything Is Marketing podcast, I spoke with The American Prospect executive editor David Dayen about how policy ideas are marketed - how does an idea move from left-leaning and right-leaning media through an ecosystem and ultimately become policy. It’s not a conversation about politics, it’s a conversation about how ideas move through a funnel, just like any product.

And of course, thanks to everyone who has become a paid subscriber to Gobbledy - it means a lot that you’re supporting this project.

This week:

Marketing death: A bold gambit that sorta pays off (I think?)

There are 2 reasons to be quiet at the library

Dying to Try Your Product

We talk quite a bit (maybe too much? Hm.) about how effective it is being the first marketer to use a medium, channel, message, whatever compared to being the 7th marketer to do something. In short, being first gives you the ability to stand out, even if your product isn’t particularly unique.

I came across a study recently that talked about death being the last taboo in advertising. (You know how I know it was talking about death being the last taboo in advertising? Because the study was titled, “Death in Advertising: The Last Taboo?”).

Because death is used so infrequently (the authors of the study call it “exceedingly rare”) in advertising, it can be very effective.

Which is not to say that marketers never used death as a tool to sell you something.

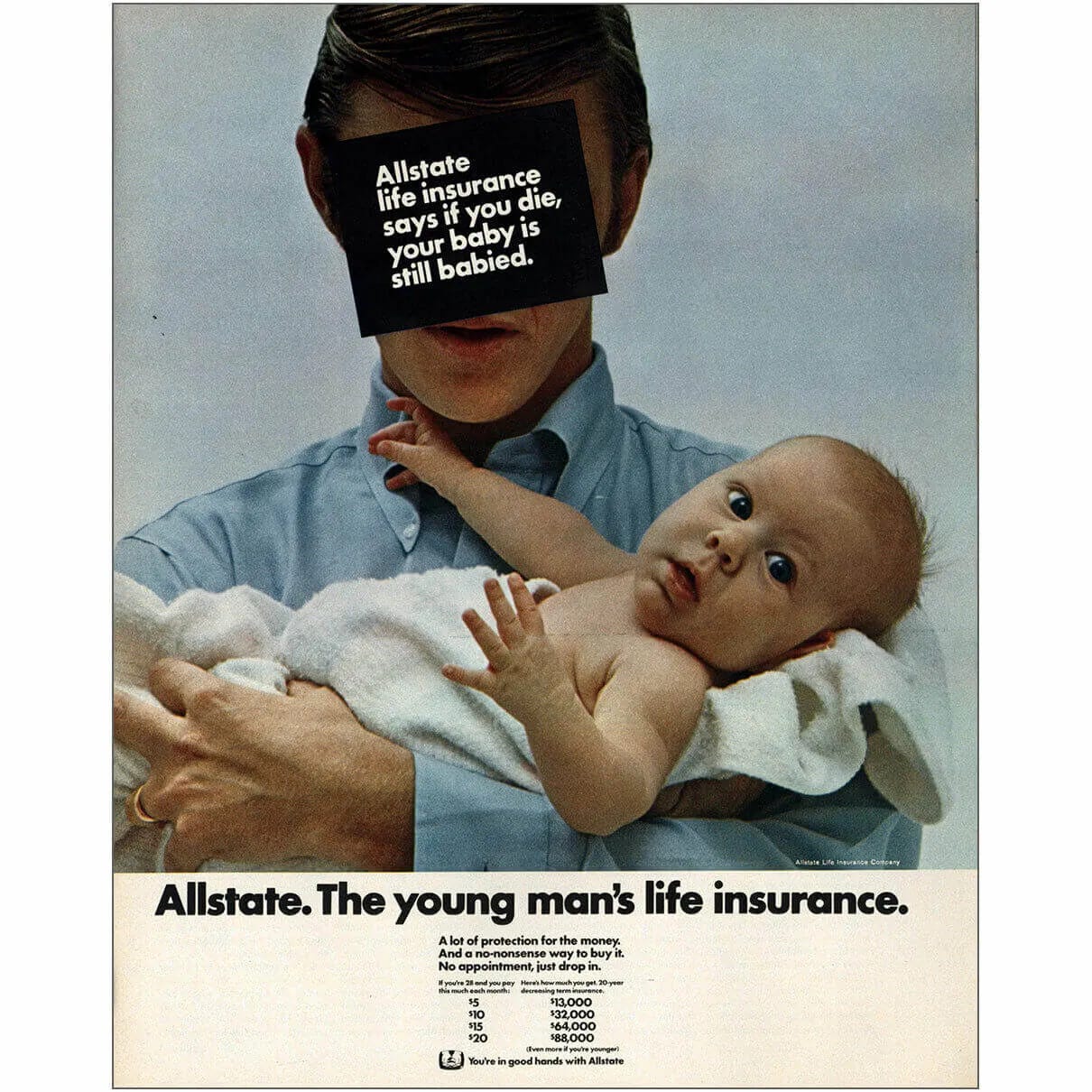

One of the first issues of Gobbledy shared the story of an Allstate Insurance campaign from the early 1970s that actually talked about dying in pretty stark language. Allstate positioned itself as the insurance for guys who just started a family, and it ran a campaign that had ads like this:

Yeah, “if you die” was there at the top. It’s pretty jarring. (It’s pretty jarring for that baby, too, if you look at his face.)

This seems to have kicked off an ante-upping “before you die unexpectedly, you should buy more life insurance” messaging war that hit its apex in 1976 when a Barbarino-era John Travolta shilled for financial services company MONY.

In this ad, he walks down the streets of New York City (without any of the swagger found a year later in the opening shots of Saturday Night Fever) and says directly to camera, “I was 10 was my father started saving for my college education…he had it all planned. There was only thing he didn’t plan. He didn’t plan on dying.” (Bad planning on his part.)

It’s a little jarring, right? You really never hear death played straight like that in an ad.

Speaking of playing straight…

Side note: Once you start searching for Travolta commercials from the 1970s, there’s quite a bit to unearth. Here are two commercials someone has put back-to-back for different products where he is showering with a bunch of guys and singing…

Anyway, where were we? Oh yes, death stuff…

The study I mentioned earlier found that unlike in those happy-go-lucky 1970s, nowadays consumers are more willing to accept death in marketing, if it “included the use of humor, non-human characters, unrealistic situations, and evocative music.”

One of the most effective marketing campaigns in recent history used all of those 4 elements to create a whole world, at first to warn people about the dangers of screwing around on Melbourne’s train system, and then spawning a whole universe of apps, games and toys. If you have children who are now 18-20, “Dumb Ways to Die” is burned into your brain:

To break it down a bit, the genius of the message is that they present a whole bunch of dumb ways to die (“use your private parts for piranha bait”) with the idea that screwing around on the train is as stupid as “getting the toast out with a fork.” In other words, we can all agree that those things are dumb ways to die, and so is screwing around on the train. It works because the examples are universally dumb and the song is catchy.

Why am I explaining all of this? Good question.

The “I-wonder-where-my-kids-are-right-now” app Life360 recently released an ad that takes a lot of what the study suggests for advertising involving death (humor, unrealistic situations, evocative music) and mushes it together into a song and cartoon about how moms are very, very worried that their children will die in crazy ways. And, hence, there’s an app that will tell you where your kids are so that you may, I guess, prevent them from getting chopped in half (or whatever).

It’s worth watching the ad - it’s clever and funny, and I’m pretty fascinated by it (and I think you will be too):

So while it seems that Life360 is taking a similar approach to the Dumb Ways to Die campaign, it’s different in two ways that I think are important:

It makes a difference that there are actual people in it, rather than just using animation. I think there’s a reason why the study suggests using “non-human characters” - for the humor to work, the traits the mom is expressing need to be exaggerated. If it’s a cartoon, the exaggeration is part of the point. If it’s a person, the mom feels, how do I put this, a little nuts. I know that’s likely not everyone’s take on the mom here. But that’s the danger of using people in an ad that uses death to make a point. Here, the daughter is the sane one and the mom is presented as a little crazy. The issue is that the “sane one” isn’t the one buying the product - the “crazy one” is. So the message is either “yes, you’re crazy, but if you have this app you’ll be less crazy.” Or it’s, “your parents are getting this app because they’re nuts.”

Dumb Ways to Die equates the dumb ways to die they mention with the dumb act of screwing around. There’s no equivalence here - the mom is worried about some crazy stuff (“you could get stuck in a mine,” getting sucked into a wood chipper, etc). The app doesn’t actually solve for any of those things - the message is basically, if you’re worried about crazy stuff happening to your kids, we’ve got an app for that.

And yet - I keep re-watching it.

I’m not sure this entirely works. But they took a big swing in a way that we rarely see — what is the real, true problem that the product is addressing?

For example - Grammarly is a tool that helps you write better. Their website describes it thusly: “Work better together with Grammarly, the trusted AI assistant for everyday communication.”

I guess the problem it says it’s solving is that you’re not working together well. I don’t know - that messaging is terrible.1 But you can imagine it also saying, “write clearer, every time you write” or something like that. That would be fine.

But what if it said something like, “never worry that someone will read what you wrote and think that you’re an idiot.” That is the underlying problem Grammarly solves. “I hate the feeling of worrying that people think I’m an idiot because I don’t think I write well.”

Rarely do products tap into the deep underlying emotion that a product addresses. Life360 went for it and put it out there - when your kid leaves the house, you’re afraid they’re going smooshed by a piece of construction equipment. Yeesh. But also, that took guts.

A Different Way to Finnish the Sentence

The New York Times ran one of those “are people really happy in that country that was ranked The Happiest Country on Earth” stories. This one was about Finland.

The story included a section about signs the author saw in libraries in Brooklyn and in a library called Oodi in Helsinki asking for quiet, and what the wording of those signs suggested:

At home in Brooklyn, the library is papered with reminders to “Please keep your voice down.” In contradistinction, the signs at Oodi said, “Please let others work in peace!” The two commands are almost — but meaningfully not — synonymous. The Brooklyn version is a plea for self-control. The Finnish version is a request to acknowledge the existence of other people. You see the difference.

As a matter of fact, I DO see the difference, and we write about that difference all the time. It’s the difference between “Fluzzio.ai helps you create ads quickly” and “Your prospects enjoy campaigns relevant to their needs. Buy Fluzzio.ai.” Focusing the messaging on the recipient is fine, but appealing to people’s empathy (“using this will benefit others”) is a more emotionally resonant message. Not as emotionally resonant as “your child may be chainsawed in half,” but emotionally resonant.

My in-laws live in a community in Florida that is beyond lovely, and we go to visit each Christmas week. Every other resident’s kids (and kids-in-law) also visit that week, and because of that chairs at the community pool are full. Also they’re full because jackasses (not you - other jackasses!) put their towels on the chairs at 7am like it’s the Holiday Inn in Tampa.

There are signs that say, “don’t save chairs” (ie, “please keep your voice down”) but I always thought that a sign saying, “Esther’s grandkids would also like to have a place to sit” (ie, “please let others work in peace”) would be more effective (to be clear, the signs are entirely ineffective.)

What I’m saying is that empathy is a powerful messaging strategy. Also, don’t put towels down at the pool.

Thanks always for reading to the end - it’s the best part.

I’m actually curious (and not in a thirsty, please leave comments kinda way) - did you think that Life360 ad worked? I’m so intrigued by it - I’d love to hear what people think…

In the 3 days since I wrote this paragraph, Grammarly has changed their homepage to “Clear writing to lighten your workload…Save time with Grammarly, the trusted AI assistant for everyday communication.” Crazy enough, that’s pretty close to what I was suggesting above.

It’s a challenging product to market.

No kid (probably) would willingly add a parent spying portal to their phone. But I also imagine many parents, although they might want to add a spy portal to their kids’ phone, would feel guilty (or ethically conflicted) doing so.

So, how do you sell this thing? Convince parents it’s within their rights and responsibility to spy on kids? Or, let parents know they’re actually not so crazy because: Look at how insane the mother in this commercial is; she’s way more anxious than you! There’s a fancy name for this sort of argument: “relative privation.” It doesn’t make sense when you think about it, but it can be fairly effective.

I have 3 teens. So that makes me an audience of 1 (3?). My kids would NEVER feed my neurosis by suggesting we use Life360. In fact they constantly try to disable Apple's Find My Phone (the only reason I've managed to use to convince them to keep it on is to actually find their phones, which, surprise, they lose).

My point: I would never use an app that fed my neurosis about something happening to my kids while they're out being kids/people. Truth is I don't actually have neurosis around that, fortunately (being married to a neuropsychologist might have something to do with it). I come from the 'Blessings of a Skinned Knee' parenting cohort.

Now if there was an app that could reassure me that they'll land on their feet and become well-adjusted, self-sustaining adults, now that I would use.